British films of the 1940s and 50s take a lot of beating. Whether in colour or in black and white, they are eminently watchable and offer so much in terms of both entertainment and snapshots of our social history.

Powell and Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944) is regarded today as one of their finest masterpieces. Beautifully-shot in the Kent countryside, the film is part whodunit, part allegory. It begins with the accidental meeting of a GI (US Army Sergeant John Sweet), a British soldier (Dennis Price) and a land girl (Sheila Sim) in the fictional ‘every village’ of Chillingbourne, on the Pilgrims’ Way. Each of them is travelling to Canterbury for private reasons, but first they must solve a local mystery. If you have not seen the film, I urge you to seek it out, if only for the fascinating shots of mills, hop gardens, farmyards and wheelwright’s shop which pepper the action.

I have seen A Canterbury Tale a number of times, but when we first started to explore the possibility of putting our three fields down to hay, about five years ago, another viewing brought me unexpected inspiration.

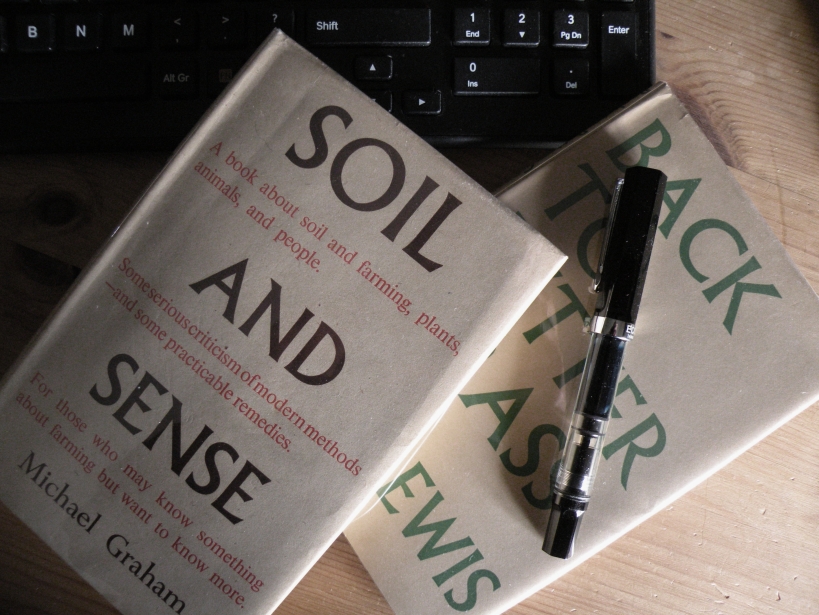

Amongst the clutter of inkstand, letter scales, packets of saved seed and a pamphlet delightfully entitled ‘Rough Stuff for Home Guards’ on the desk of a local farmer and historian (Eric Portman), lies a copy of Soil and Sense by Michael Graham.

I was intrigued, and was soon able to track down my own copy.

Soil and Sense was three years old when the film was made, having been published by Faber in 1941, but its content could hardly be more relevant today, when soil health is – or should be – so high on the farming agenda. As far as I can tell, Graham wrote exclusively on ecological and farming matters. He was one of a number of wartime writers who feared that the push for production at all costs presented severe danger to the future health and stability of the soil itself. He expressed the view that public money paid towards agriculture ‘should go to good farmers who feed the land as tradition says it should be fed and … none should go to those who merely exploit it.’ He believed the future of farming was bound up in the relationship between grass, pasture and livestock; he has been called a ‘muddy-hoof’ ecologist. His work is all the more remarkable when one remembers that he was writing decades before the mycorrhizal associations between plants and soil fungi were widely understood.

Graham’s book was one of several published by Faber during the Second World War with a focus on farming and the countryside, each slender volume produced on crude, flimsy paper in deference to wartime restrictions. I have sought out some of the other titles since – the one in the picture above is Back to Better Grass by I G Lewis (also Faber, 1942) – and followed-up with more recent information, too, but it was Graham who first introduced me to the art and science of establishing and managing grassland for soil health. His book, and in particular the diagram below, so elegant in its simplicity, became the cornerstone of our plans.

© Three Fields of Hay 2017